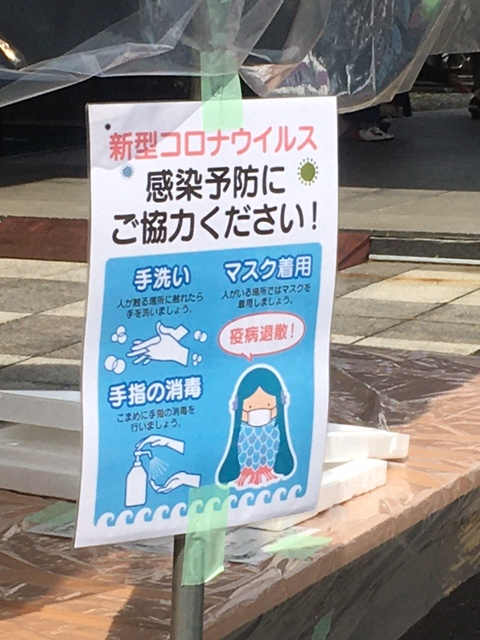

If you live in Japan or have been following Japan-related news, you’ve probably seen the mermaid-like creature on Sobacchi’s right at some point. It’s on announcements from the Ministry of Health, is sketched or pasted onto PSAs from businesses large and small, and is all over social media.

But what’s it doing here all of a sudden?

This creature is called Amabie (pronounced ah-mah-bee-ay), and it’s a folkloric being known as a yokai.

In Japan, yokai are somewhat comparable to the fair folk (or classical fairies) in Europe. Like fairies, yokai may be large or small, bold or shy, human-like or animalistic: at times benevolent, mischievous, or wicked towards humans. All this depends on the storyteller, time, and place.

In the case of Amabie specifically, according to legend it emerged from the water in what is now Kumamoto, hundreds of years ago. Amabie told the person who saw it that if its image was recreated and shown to others, it would provide protection from disease. Since then, during various epidemics in Japan, people drew and displayed Amabie, almost as a part of infection prevention measures. But it’s been decades since the last pandemic, so Amabie faded into obscurity amongst the countless other yokai legends.

This year, though, Amabie is anything but forgotten.

Since Amabie is having its moment in the spotlight, I wanted to learn more about the lore surrounding them through immersion in yokai country. Fortunately, just such a place is right next door: Tono, Iwate, the city of folklore.

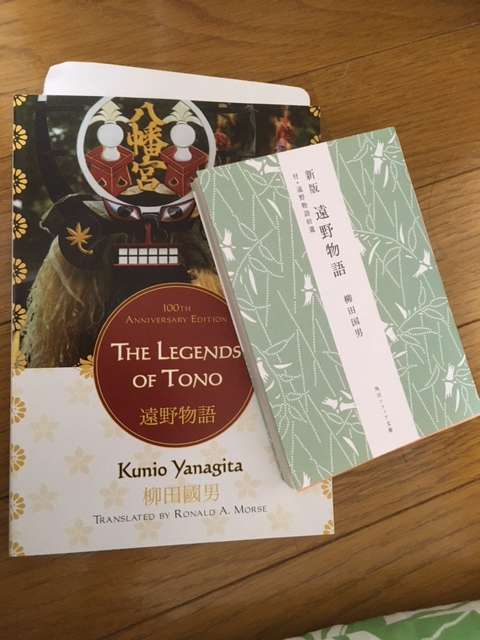

Tono got this name thanks to the work of Kunio Yanagita and Iwate-born Kizen Sasaki, who collaborated to write down the folk tales that Sasaki had heard in his childhood. By recording these tales, they elevated Japanese folklore into something that could be studied and distributed, and thus have a similar role in Japan to the Brothers Grimm.

Tono is said to be home to one of the most famous yokai: the kappa, a mischievous, humanoid, turtle-like creature that loves cucumbers and lives in rivers. Kappa appear in all kinds of popular media, from Japanese anime and video games to Harry Potter.

If one imagines where yokai might hide if they were real, Tono, with its abundant hills, forests, and streams, would be the perfect place. My first stop was Kappa-buchi or Kappa Pond (though it’s actually more of a stream.) The rush of water and the rustling grasses certainly made it seem like something could be living here, and I couldn’t help but almost wish there was, against my skeptical tendencies. The fairytale atmosphere led me to sit by a fishing rod with a cucumber attached and watch the water for some time, but alas no kappa emerged.

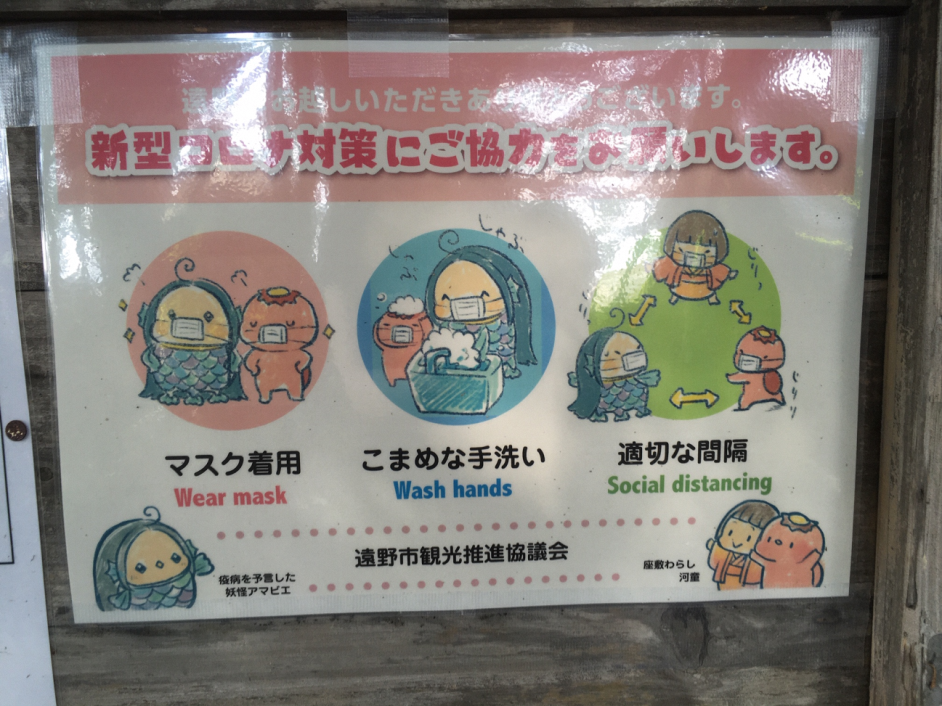

Next stop was Denshoen, the Folklore Museum, with a notification poster featuring Amabie and a kappa practicing good prevention tactics at the entrance. Although there wasn’t much info about Amabie, there were plenty of interactive exhibits about all kinds of stories, plus a timeline (in English and Japanese) about Kizen Sasaki’s life.

The gift shop carries The Legends of Tono in English and Japanese, both of which I happily snapped up. This book gave me a lot of insights for this article, so I really recommend it.

Finally, I stopped at a michi-no-eki – literally “road station,” a kind of homespun, Japanese-style roadside rest stop – for a quick bite to eat before heading home. In addition to a ton of kappa-related souvenirs, I also spotted this adorable Hello Kitty kappa, with a mask (of course.)

Speaking of Hello Kitty, Japan is somewhat well-known at this point for making mascots for almost everything, from gas companies to banks to the census or social security. A cute mascot can make a complex, stress-inducing concept more approachable. For me at least, a poster with a kind-looking Amabie will quickly catch my eye and give me a bit of peace of mind while following the rules.

To return to Amabie, I think it’s significant that the idea to create an image as a way to ward off illness would persist, illogical though it may be. It makes a sort of sense to craft an image of a protector, especially back when most diseases were mysterious and dreadful. Besides, I believe creativity can be a helpful coping mechanism in unpredictable times like these, so drawing this image may have been a comforting, meditative experience for the people of the past.

With that in mind, I decided to try my hand at drawing Amabie. I’m not much of an artist, but there are plenty of references and how-to videos online, and after a few tries, I created an image to be (more or less) happy with.

Japanese

アマビエについて~伝承、妖怪のお話~日本では今、人魚のような生き物(そばっちの右側のキャラクター)を様々なところで見かけます。SNSはもちろん、私の住む奥州市ではポスターや南部鉄器のモチーフにもなっています。厚生労働省ではロゴを作りました。

しかし、なぜ急に目にするようになったのでしょうか?

この生き物は「アマビエ」という、日本に伝わる妖怪です。

日本の妖怪は、ヨーロッパでいうfair folk(伝統的な妖精)に相当します。Fair folkのように、妖怪の種類は豊富で、大きかったり小さかったり、大胆だったり内気だったり、その形も人間だったり動物だったり、いたずら好きだったり害をなしたり、様々あります。

アマビエは、伝説では、数百年前、今の熊本県の海中から姿を現し、豊作や疫病の流行を予言し、見た人に「自分の姿を描き記した者は疫病から逃れることができる」と告げたと言われています。

今年は、コロナウイルス対策としてアマビエの姿を描こうという動きが、日本に広がっているのです。

アマビエをきっかけに、妖怪に興味を持ち、伝承をもっと知りたくなりました。幸運にも、私の住む奥州市の近くには、民話の里で知られる岩手県遠野市があります。

遠野市が「民話の里」と呼ばれるのは、柳田國男の名著「遠野物語」のおかげです。遠野物語は、遠野地方出身の佐々木喜善より語られた遠野地方の伝承を柳田が書き記したものです。グリム兄弟がドイツの昔話集を編纂し、グリム童話としたことに重なると感じました。

遠野市はもっとも有名な妖怪の一つの河童の里と言われています。河童は、いたずら好きで、まるで亀のような甲羅を背負った人間のような形で、キュウリが大好きで川に住んでいる妖怪です。河童はアニメやゲーム、童話など様々なメディアに登場します。

妖怪への思いがつのり、遠野市に行きました。里山、森、川など自然が豊かでした。

最初に向かった河童淵。さらさらと流れる水とさやさやしている草は、何かがここにいるのではないかと考えさせられました。河童などいる訳はないと思いながらも、いて欲しいとさえ感じました。幻想的な雰囲気の中、キュウリを吊るした釣り竿のそばに長い間腰掛けて水面を眺めましたが、やはり残念ながら河童には出会えませんでした。

次は伝承博物館の伝承園。入口で感染症対策をしているアマビエと河童のポスターが掲示されていました。アマビエについての情報はあまりありませんでしたが、色々な物語の双方向の展示はたくさんありました。しかも、佐々木喜善の生涯についてのタイムライン展示は、英語・日本語の両方ありました!

売店では、英語のお土産も置いており、楽しく買い物をしました。この記事を書くためにこの本を参考にもしました。お勧めです。

最後に、道の駅に立ち寄り、家に帰る前に軽食を取りました。たくさんの河童のお土産が並んでいる中で、このかわいい河童キティちゃんに目を引かれました(マスクをつけているのはさすがです)。

キティちゃんといえば、日本では数多くのキャラクターやマスコットがあることが特徴的です。企業や金融機関、国勢調査などにもイメージキャラクターがあります。日本と違って、アメリカのイメージキャラクターはスポーツチームやレストランを代表するなど比較的に主要じゃない役割を持っています。日本に来る前は、イメージキャラクターをほとんど考えてなかったです。

かわいいキャラクターで身近に感じさせ、ストレスを下げるように思います。私の経験では、アマビエのあるお知らせは優しい印象で、安心して内容を読むことができます。

さて、アマビエに話しを戻します。絵を描いて病気を防ごうという考えが続いているということは興味深く思います。医療や公衆衛生が発達していなかった昔、恐ろしい病気からの救いを絵に求めたことは理解できます。希望は、今も昔も人々が前に進もうとする力とも言えるかもしれません。

私もアマビエを描くことを挑戦しました。絵を描くのは得意ではありませんが、ネットを参考に試行錯誤し、自分なりに満足できる絵を描けました。コロナウイルス感染症が一刻もはやく終息しますように。

-195x124.jpg)