As those of us here in Iwate welcome the winter months, everyone wants to make their indoor spaces as warm and cozy as possible. Rustic home cooking is a great way to do that, especially as we all spend more time at home rather than eating out. But what does Japanese comfort food look like?

When someone says “Japanese food,” something along the lines of an elaborate sushi platter with tempura probably comes to mind first of all. Of course, dishes like that are a wildly popular part of Japanese cuisine that regularly hit the top of favorite food lists. But the average person is more likely to eat these foods at a restaurant or while celebrating a special occasion, as opposed to, say, an ordinary night in.

Everyday foods in Japan are more approachable than sushi and less time-consuming than tempura. Dishes are straightforward and health-conscious, with an emphasis on rice, vegetables, and whatever the local area has to offer.

Iwate is bigger than it looks on a map – it’s a prefecture that covers a lot of ground, and includes mountains and their foothills, coastlines and southern flatlands, so the food traditions here vary quite a lot. Depending on the season and region, our specialties include fresh seaweed, Pacific saury straight from the ocean, wild mountain grapes and vegetables, milk and yogurt from our numerous dairy farms, buckwheat noodles prepared all kinds of ways, famous Maesawa wagyu beef, and much, much more than I have time to list here.

Anecdotally, I’ve noticed a few quirks of Iwate food culture. For one thing, compared to other prefectures Iwate doesn’t shy away from meat. This tendency can be seen in the popularity of well-known dishes around here like Iwaizumi horumon-nabé (offal hotpot), Tono jingisukan (grilled lamb and vegetables), and the ubiquitous yakiniku restaurants where customers cook their own meat on small grills in the center of the table. (These restaurants frequently offer Morioka reimen alongside.)

Another characteristic of Iwate cuisine is a love of natto. Natto – sticky fermented soybeans with a pungent and protein-filled kick – is a breakfast favorite in homes across Japan, but it’s especially popular here. It’s added to rice, noodles, toast, and almost anything else you can think of. The distinctively strong flavor and texture make it an acquired taste, but it’s so healthy and versatile that I highly recommend giving it a chance.

In fact, it’s a common addition to the first dish I want to talk about in detail: tamago-kake-gohan, sometimes abbreviated TKG: or, egg on rice.

A fresh raw egg on top of rice, seasoned with seaweed flakes and a splash of soy sauce.

A fresh raw egg on top of rice, seasoned with seaweed flakes and a splash of soy sauce.

You’re not likely to find this in a restaurant, mostly because it’s devastatingly simple: crack a raw egg* over rice, add soy sauce/other garnishes, stir well, enjoy. But it’s a filling, no-fuss way to start the day. Toppings like seaweed flakes, salt, mirin, or natto (or all/some of the above) elevate the dish by providing a satisfying burst of umami from the first bite to the last.

*Worry not – raw eggs are safe to eat in Japan.

To go back to Iwate food culture in particular, grilled lamb from Tono is well-established as a regional specialty, but what’s less well known is that Oshu is becoming a key player when it comes to raising sheep for lamb and mutton. As Iwate continues to accommodate people of various faiths and cultures, both as visitors and as long-term residents, we might start seeing more mutton and lamb dishes catch on in the future.

A proper jingisukan involves a small, specialized grill, so it’s not easy to make at home. That’s why I like to make a stir-fried version with local Oshu lamb and vegetables. It may look complicated, but it comes together quickly, the ingredients are not too expensive, and it’s absolutely delicious. (Recipe at the end.)Homemade jingisukan style stir fry.

Homemade jingisukan style stir fry.

As for a dish that’s both a winter treat and an Iwate specialty, there’s hittsumi (or hatto, if you’re in southern Iwate). It’s a hearty stew that, in addition to standard ingredients like meat and vegetables, features soft flour dumplings of the same name. It’s comfort food, pure and simple. I’ll admit it was a bit of a project for an amateur like me, but the end result was more than worth it. I used this recipe, which has been translated into English by Rock on Iwate (a Facebook page that promotes Iwate in English.)

Rock on Iwate – Hittsumi recipe in English

(Original recipe in Japanese: http://i-namamen.com/hittsumi.html)

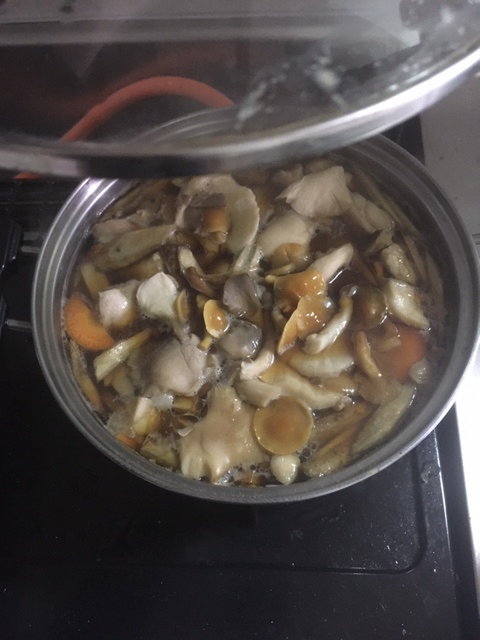

Southern hittsumi simmering in a pot. Hittsumi dumplings not pictured.

The finished product!

Cooking Japanese food might be intimidating at first, but there are all sorts of websites and YouTube channels dedicated to introducing Japanese home cooking in English. When I first moved to Japan and began living in rural Iwate, I knew the very basics of Japanese cooking but had done hardly any on my own. As I got more used to it, I found that using ingredients from the same land I lived on created feelings of connection and belonging. Something about making comfort food isn’t just physically nourishing, but psychologically as well. And of course, there’s the most important element – it tastes delicious.

Jingisukan-style Stir Fry (translated from Kurashiru. Original Japanese:

https://www.kurashiru.com/recipes/cc36c7cc-6066-45b5-905b-5785546fb069?search_type=next)

Serves 2

Main

– Lamb (200 g)

– Cabbage (4-5 leaves)

– Bean sprouts (50 g)

– Chives (3 stalks)

– Salt and pepper to taste

– Cooking oil (1 tablespoon)

Sauce

– Cooking sake (1 tablespoon)

– Mirin (1 tablespoon)

– Honey (1 tablespoon)

– Soy sauce (1 tablespoon)

– Miso (1 tablespoon)

– Grated garlic (1 cm)

– Taka-no-tsume pepper to taste

- Slice the cabbage into largish pieces, and cut the chives 3-4 cm long.

- Cut the lamb into bite-sized pieces and lightly add salt and pepper.

- Combine all the seasonings for the sauce in a bowl.

- Heat cooking oil in a pan and place the lamb in it, on low heat.

- Once the lamb is browned, remove from the pan and add the vegetables. (Add additional cooking oil here as needed.)

- Once the vegetables have softened up, put the cooked lamb back in together with the sauce. Quickly cook them all together on medium to high heat and serve piping hot.

Japanese

岩手のソウルフードで冬を乗り越える~寒い日々こそ郷土料理を~

岩手にいる私たちは冬を迎えるにあたり、できるだけ温かく心地よい生活空間を求めます。その雰囲気作りのため、郷土料理を自分で作ろうと思いましたが、日本の「ソウルフード」とは何でしょうか。

「日本料理」と聞くと、ほとんどの外国人はおそらく、最初に思い浮かぶのはお寿司や天ぷらでしょう。これらは確かにアメリカでは「好きな和食」の第1位としてよく見ます。しかし、日本では家庭で毎日作っているというわけでもなく、お店で食べたり、何かをお祝いするために食べることが多いと思います。

日本の家庭料理はお寿司より敷居が低く、天ぷらより手間のかからないものが私の好みです。素朴でヘルシーな、ご飯、野菜にその地方ならではの味です。

岩手県は地図で見た印象より広く、山地とそのふもと、複雑な海岸線、北上川に由来する平地など、様々な表情を持つ県です。食文化も様々で、それぞれの季節や地域で私たちを楽しませてくれる名産品があります。鮮やかなワカメ、水揚げされたばかりのサンマ、山葡萄、山菜、牛乳やヨーグルト、蕎麦など、書ききれないほどあります。

また、岩手では肉料理も豊富です。岩泉ホルモン、遠野ジンギスカン、焼肉店(盛岡冷麺も一緒に食べられます)などは人気がありますし、前沢牛のようなブランド牛もあります。

さらに、岩手の特徴は納豆が人気です。全国でも広く浸透している朝ご飯の定番が、岩手では特に大人気です。ご飯、麺、トーストなど様々な料理に使用されています。独特の濃い味や触感があり、好みが分かれる食べ物ですが、ヘルシーで色々な料理にも合うので是非試してみてください。

ここで、詳しく紹介したい料理があります。卵かけご飯(略:TKG)です。日本全国にも多くのファンがいることでしょう。

[写真:手作り卵かけご飯]

超簡単~ご飯に生卵をかけ、醤油などをたらし、混ぜれば出来上がりです。レストランでこれを食べることはまずないでしょう。でも手がかからずに、お腹いっぱいで一日を始められます。ふりかけ、塩、みりん、納豆などの調味料を使って、旨味を楽しむのも良いでしょう。

岩手ならではの話に戻すと、遠野のジンギスカンは知られていますが、奥州市の羊が近年、注目を集めつつあります。岩手県で色々な文化・宗教の観光客などを迎え続くことになれば、私たちも羊料理を口にする機会が増えるかもしれません。

ちゃんとしたジンギスカンを作るには、専用の鉄板が必要であり、家で作るのにはちょっと難しく、家庭用フライパンで調理できる奥州産ラム(仔羊)肉と野菜炒めバージョンをよく作ります。仕込みは簡単で、材料代もそれほど高くないし、何より美味しいです。(レシピはここ:https://www.kurashiru.com/recipes/cc36c7cc-6066-45b5-905b-5785546fb069?search_type=next)(英語版は英語記事にあります。)

[写真:ジンギスカン風ラム肉の野菜炒め]

冬の岩手の名物といえば、はっと(地方によっては「すいとん」や「ひっつみ」などといいます)でしょう。小麦粉に水を加えてよく練り、熟成させて薄くのばした生地を茹で上げるという郷土料理、ソウルフードです。地域や家庭ごとに調理法は異なります。初心者の私にとって、作るのは正直大変でしたが、苦労した甲斐があるほど良い出来上がりでした。

ロック・オン・岩手という英語PRページのレシピを参考にしました。

Rock on Iwate - Hittsumi recipe in English

(日本語レシピ:http://i-namamen.com/hittsumi.html)

和食を作るのは、慣れないと大変かもしれませんが、和食の作り方を英語で詳しく紹介するサイトやユーチューブチャンネルは多くあります。私が岩手の田舎に暮らし始めた頃は、ほとんど自分で和食を作れませんでした。でも住み慣れていくにつれ、私と同じ環境、同じ土や空気や水で育った地域の食材への親近感が増し、地域との繋がりや連帯感の気持ちが強くなりました。不思議なことですが、郷土料理というものは、単なる肉体的な栄養だけではなくて、心にも届く「栄養」と言えるかもしれません。もちろん味も最高です。

-195x124.jpg)